Whose Work Is It?

- lastcathar

- Dec 30, 2014

- 9 min read

Students are up to their necks in expectations. Family, school, advertising, religion, hormones... all make demands on them, on their attention, on their energy, and also on their individuality.

As teachers, we can't help but add to this burden. It is, after all, Neitzsche's parable of the camel, the dragon, and the lion. But we are in a unique position to give meaning and a sense of purpose to our students' labors.

Joseph Campbell has a message for us: Our students accept the load with the expectation of becoming lions. This may, in their imaginations, take unrealistic forms like wealth and fame, love and glory...but these are more than just silly daydreams, they represent a desire to be an important participant in society, in the world.

Those imaginings are symbolic. Young people see the masks worn by the leaders of society, and want someday to wear those same masks themselves.

This is not something teachers need to fight. We need to use it, take advantage of it, and help them to build the foundations their "castles in the air" will need. As long as students feel engaged in the education process, as long as they get a sense that the class load has some connection to their vision for their own future, then they will try. When the work seems to take them no closer to a leonine future, when it starts to seem like busy-work, then you lose them, and rightly so. They should demand better instruction than that.

But how can we make them feel the connection between calculaus, for example, or Huckleberry Finn, and the BMW of their dreams? For starters, we can find ways to make the work theirs, not work done merely for us. In other words, we can give them ownership, real engagement in schoolwork.

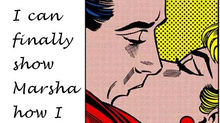

I get a lot of mileage out of photographs and music videos. A carefully chosen image, moving or not, can deliver an intellectual wallop on a tight budget of time and mental effort. But I am extremely selective, so much so that I frequently have to create the material myself. I also set up exactly how the material is to be used. I am a great believer in student-centered, active learning...but I know from experience that it only works if it is carefully arranged in advance.

Matthew Arnold said something like, "Freedom is a horse, but a horse is meant to go someplace." In the teaching biz, the term "student centered" does not mean "teacher irrelevant." At least in my classroom it ends up meaning that I do a ton of work before and after class in order to assure that the desired learning happens, but during class time itself, I just hang around, answer questions, and just sort of keep things pleasant. Arnold is saying that a horse without reins will not end up going anyplace at all, it will just wander and graze. Before you let students run, put reins on them, to steer 'em in the right direction.

Here's an example:

I show 3-minute a film about Frida Kahlo...

...Then I say, "so, like, get a partner. Here's your task: based on this little video, what do you guys know about Frida Kahlo?"

From the students' point of view, this seems like a wide open opportunity to think critically about the meaning of these images. Most of my freshmen have never heard of Kahlo, so the topic itself opens up a new world. But I have already framed their task: "What do you know about her, based on these images." This simple question has the effect of eliminating a lot of dead-end ways of approaching the material. I do not want the students to think about whether they liked the images. That would be a mindless exercise requiring no critical thought, no effort at interpretation or meaning-finding. I want them to look for something that is under the surface, something they felt more than saw in the film. I want them to make unique and very personal discoveries, and be able to give clear explanations of how they arrived at their ideas. The simple question that framed the task serves to direct their activity without reining-in their creativity.

For example, a student might say, "She is confused," and cite The Two Fridas

...or say, "She is in pain" and cite The Little Deer

They are thinking critically, "reading" the visual documents critically, and constructing arguments. The more ways they exercise these thinking and reasoning skills, the more thoroughly they learn them, and the more range they will have in applying these skills in a variety of situations for the rest of their lives. Doing this work in pairs makes it social, and it gives them a two-heads-are-better chance at coming up with some cool observations. And best of all, it is all theirs. I am not telling them, not lecturing, not loading them with a list of expectations, not pronouncing right-and-wrong judgments, not making them follow some Byzantine series of steps or dictating the form the final result has to be in, I'm just stepping back and letting them run.

Often, students are not used to this. But they learn to like it. Working in pairs, and then each pair standing to tell the class what they figured out, allows them to engage with the material critically and creatively, and to interact with the rest of the class non-judgmentally. There is no right or wrong answer, just thinking, discussing, finding ways to put ideas into words. And there is no threat or grade or judgment. They totally engage with the material, and totally own the results.

Once the task is running, I can just lean back and enjoy the ride.

Once it is running, that is. My hard work happens at home, where I spend long hours designing these activities, balancing my own objectives with their tastes and my range of knowledge. In this case, Frida's work was very autobiographical and powerfully emotional, so I knew that saying "what do we know about her" would be enough to spark rich discussions. (This example was my first You Tube video, made in '09. It is by far my greatest hit, with 120,000 views, 500 likes, and gillions of comments (most in Spanish). I also built the two earlier videos on this post, because I could not find anything satisfactory on You Tube to serve the purpose of this blog.)

This is not exactly Bloom's Taxonomy. I do not start by telling students how to look at art or how to construct arguments or any other specific guidelines or expectations. Instead, my guidance is minimal, while their mental effort is freed and thereby also maximized... and that mental effort is the "weightlifting for neurons" that leads to intelligence. If I taught students only to do things the way I told them to do it, they would get mere training, more Pavlov than Piaget. My approach is more Elbow-esque: These tasks are basically freewrites, but with a little direction, a purpose to help get students focused. It is "Writing Almost without Teachers" in small groups. In the course of a semester of Comp II the students may do thirty of these, adding up to a huge practice-feedback spiral, as I think of it, that begins by just speaking a few words before the whole class, and ends by building short films and entire websites for the whole world to see, about a topic of choice.

When I say practice-feedback spiral, I'm referring to something much like Torrance's Incubation Model of learning, and more directly akin to Kolb's idea of Learning Styles. Both refer to a cycle of feedback and adjustment leading to a new product. I simply envision this as a spiral because it keeps not just going around, but going upward, the product keeps getting better. But in the example I've been talking about here, the feedback comes in the form of each students observing eath others' work, hearing what everybody else had to say in their own efforts, sharing their own and each others' work. Just that. When students are really engaged, they are not all that open to criticism. And they should not be. It is their work and nobody else's. They are, however, aware of possibilities. Seeing each others' work they will make internal comparison, come up with new ideas and make their own adjustments...freely, without external comparison, without facing any overt judgment. It is not about grades, it is about the students themselves getting new ideas. They are engaged, they are directing their own learning, and from their interaction with the material and with each other, they develop and grow.

This has the effect of developing students' confidence, not in their skills, as if what they can do now is the absolute final determiner of their grade and their ability. Instead, they develop confidence in their "Ability in the abstract," as Joseph Conrad called it in Lord Jim, their absolute capacity to do anything they put their minds to. They learn that they can learn anything. They develop confidence in their ability to develop.

I've now gathered thousands of usful images, made hundreds of videos, each designed to be entertaining and engaging while serving a very specific function in my lessons. Each of these videos remains useful semester after semester, but it can take many hours to find the material and put together the package, which may also involve handouts, some little set-up statement, a clearly defined task and, always, very specific intended learning. If the students do the task, the learning will happen.

Finally, in the classroom, it operates effortlessly. I just say a few words and then preside over a room full of murmuring scholars. Last semester, in fact, one of my students complained in the End of Course Evaluation, "Mr. Steed didn't teach us nothing all semester. We had to teach ourselves while he just walked around the room cracking jokes every day." I loved that comment, LOVED it. It meant my system was, in Steinbeck's words, "spinning in greased grooves."

This is all fine and large, but we must face the music when administrators want to know what the heck is going on in our classes. I teach writing, so the intended learning outcomes are all about communication skills. Below, I've copied part of the 2013 WPA Outcomes, and bolded those that were built into this example activity.

Rhetorical Knowledge…By the end of first year composition, students should

Focus on a purpose

Respond to the needs of different audiences

Respond appropriately to different kinds of rhetorical situations

Use conventions of format and structure appropriate to the rhetorical situation

Adopt appropriate voice, tone, and level of formality

Understand how genres shape reading and writing

Write in several genres

Critical Thinking, Reading, and Writing…By the end of first year composition, students should

Use writing and reading for inquiry, learning, thinking, and communicating

Understand a writing assignment as a series of tasks, including finding, evaluating, analyzing, and synthesizing appropriate primary and secondary sources

Integrate their own ideas with those of others

Understand the relationships among language, knowledge, and power

Processes…By the end of first year composition, students should

Be aware that it usually takes multiple drafts to create and complete a successful text

Develop flexible strategies for generating, revising, editing, and proofreading

Understand writing as an open process that permits writers to use later invention and re-thinking to revise their work

Understand the collaborative and social aspects of writing processes

Learn to critique their own and others' works

Learn to balance the advantages of relying on others with the responsibility of doing their part

Use a variety of technologies to address a range of audiences

This little activity involves layers of learning. In the course of a semester, the desired learning outcomes are met in waves and cycles. Students will hit all of them many times, from different angles, in different assignments big and, like this one, small. They will come out with a clear understanding of all this stuff, though I rarely burden them with the admin-speak wording in which the WPA Outcomes are written. They learn in an organic, natural, experiential way--active learning.

But ownership and engagement can be easily obstructed. A student-centered classroom is never a student-only classroom. It needs, absolutely must have, a guiding hand, but...covert, sort of black-ops, setting up the pieces and then letting nature take its course. To interject some external, foreign list of expectations is to turn students into objects, products, units in some statistic. It destroys the ownership that leads to engagement, and ultimately it diminishes the learning it "proves." All of a sudden, it isn't about the student discovering, it's about the student meeting a requirement. The student's ideas are then of no value; the Learning Objectives--a concept entirely foreign and meaningless to freshmen--get center stage. Right and wrong answers are easier to measure objectively. Result: the classwork is about the teacher, the school, the Dean, the budget... it is about everything but the student.

Teachers have to do this double-dance. Meeting administrative requirements is a reality of the teacher's job: we have to be able to demonstrate how we have met expectations. But statistical representations of learning are just that: statistical. Real learning is a human thing, a very personal and individual thing, not a factory product. Students will only grow--and growth is the best definition of learning I know--if they are not held down. They are explorers, mapping out a new world. But whose world is it? If we want them to keep coming back, and finally graduate, we need to make them feel that it is their world.

Comments